The Philippines is a country steeped in ironies. And even more so when we deal with gender and sexuality, when womanhood and women’s bodies are on the line, when LGBTQIA+ rights are on the table.

Catholic conservatism would top the list of reasons why¹, as it has always assumed a protective stance over the woman, even as it is the first to impose restrictions on her freedom of expression. But this conservatism has never been so tested as with the fight for LGBTQIA+ rights, given the hard line drawn against the community’s right to… well, just be, and even more so, to love.

Former president Rodrigo Duterte, whose governance was buttressed by his criticism of the Catholic Church, would to some extent echo this kind of conservatism. For six years, from 2016 to 2022, Duterte was able to sell himself as someone who sought only to protect Filipinos from the evils of society — from drugs to communists — and we imagine that protection extends to women. Yet often enough, he objectified women on live television, offered female celebrities to soldiers², planted one on the lips of a random female fan³, made light of and justified rape⁴, and ordered soldiers to shoot women rebels in the vagina⁵.

That his main social media propagandists were made up of women, a transwoman, and a gay man⁶, all of whom called him “Tatay Digong” (father Digong), is important to mention: this is the father figure they built for the nation, these female, gay, and trans propagandists so empowered by a president who, often enough, revealed himself to be a misogynist and homophobe.

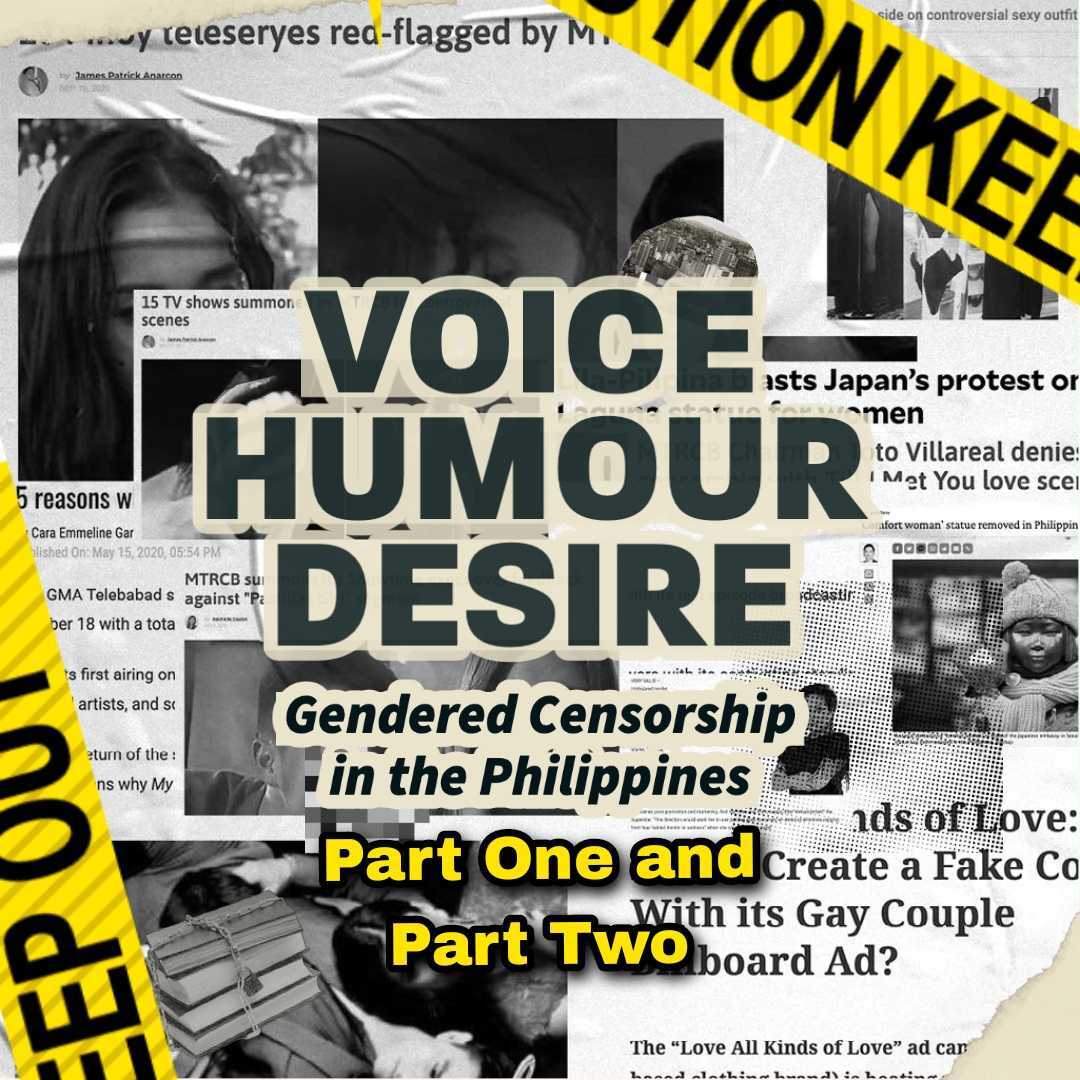

This kind of double-speak is at the heart of the kinds of artistic censorship that have targeted women and LGBTQIA+ artists for years in the Philippines. This is no surprise, when one considers that a government agency such as the Movie and Television Review and Classification Board (MTRCB) exists at all. A body that purportedly only “classifies” and rates movies and television shows for public viewing, it also in effect decides what can and cannot be consumed by the public, censuring words, acts, and clothing that it deems “offensive,” (undefined as that is). The body has also encouraged “self-regulation” which, for all intents and purposes, is self-censorship. It is in this landscape where the task of “protecting” citizens, has been about the censure of women’s voices and LGBTQIA+ desires.

But what might be important to highlight is how, as with much of our contradictions, there is rarely any space to flesh out these instances of censure, which are often peculiar, ultimately incongruous. As such, this history of gendered censorship is one that’s unwritten, and now easily drowned in the glut of the internet, forgotten as quickly as we scroll down our feeds.

Censorship is an act of erasure. And in the Philippines, we also deny it even really exists, using as proof the fact that free speech and expression are protected by the Constitution. Now layer that with the fact that gendered expressions are the ones also constantly censured — both by the MTRCB and civil society — even as these acts of suppression are also consistently silenced. These multiple layers of disappearance should not be lost on us.

So here, an effort at surfacing cases of artistic censorship in the past decade or so, that recall how certain voices, specific types of humour, and most forms of desire, are deemed unacceptable artistic expressions — unfit for public consumption and discourse.

This week, we add another six cases to the ones uploaded last week.